Economists around the world posit that carbon pricing is the holy grail to realise all necessary efforts towards combating climate change. Doing so creates a negative externality which then forces the emitters to correct their supply chains in favour of a net zero target eventually with an increasing carbon price.

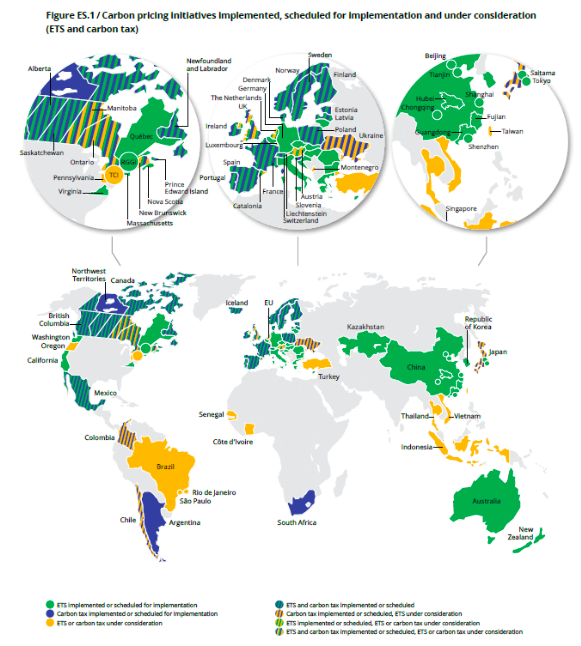

But what experts and governments don't seem to agree on is the better instrument to manifest the carbon pricing. Carbon tax and ETS/emission trading schemes (or emission allowances or cap and trade programs) are the two clear forerunners in this debate. Below is a global map depicting the regional variation of carbon pricing paradigms implemented using both these tools.

In this article, we analyse the underlying dynamics of each and try to understand what causes a particular regulator to side with one over the other. The crucial part to note is that in carbon pricing, regulators have a choice between regulating either of price or volume. The other gets correspondingly adjusted through subsequent market discovery.

Dynamics of a Carbon Tax scheme

In a carbon tax regime, emitters are charged a fixed fee for every ton of GHG emissions produced. By charging a fixed fee, and having ascribed a value for that fee, the regulator basically sets the price for carbon emissions in the market via carbon tax.

Consequently, as discussed the market is then left to decide where exactly to invest in order to reduce their emissions so as to offset the brunt of increased costs of emissions.

Pros:

- Carbon tax incorporated as an additional tax in the existing administrative setup is easy to implement

- Since emitting corporates can reliably predict their outflows towards carbon tax, it becomes easier to evaluate the investments needed to be undertaken for reducing their emissions

- It provides the corporates a flexibility to evaluate where and when to invest to reduce their emissions. Arguably, it incentivises them to make do with elements of their value chain creating the least economic value, post adjusting for their contribution towards a corporate's net emissions

Cons:

- It is not possible for policymakers in a carbon tax regime to reliably achieve a certain emission reduction target for their own NDC (nationally determined contributions).

- Closely related to the previous point, the emission reduction quantity may have a significant inelastic component involved w.r.t. emission price. So it might not be useful at all in inefficient markets with weak correlations between price and supply.

Dynamics of an Emission Trading Scheme

As covered in detail in a previous blog, an ETS involves a policymaker setting a market wide cap on the total allowances. These allowances are then allocated to specific industries or corporates via spot market auctions.

Evidently, ETS is in a way achieves the carbon pricing via regulation of quantity of emissions. The price is determined by the market subsequently. For entities for whom the price of decarbonisation is currently more than the ETS market price, they'll prefer to buy the latter from the market. The dynamics is reverse in the contrary case.

Pros:

- Helps policymakers reliably reign in the rate of emissions reductions to align with their net zero targets

- By capping the market wide allowances, policymakers help create efficiency in the process of decarbonisation by penalising those with the higher decarbonisation cost to effectively rewarding those with a lower cost of decarbonisation

Cons:

- By virtue of price discovery being a market phenomenon, it is hard for corporates to reliably estimate the future costs of their emissions.

- This also translates to an increased complexity in determining their underlying expected cost of capital and therefore the viability of investments towards a net zero strategy

Which is better then?

The reason that policymakers have zeroed in on a particular flavour of carbon pricing through some combination of the two, is driven as much by the local political landscape as by the underlying economics of the two instruments. For instance, it might be harder in certain regions more than other to impose a carbon tax, given the adverse connotations of increased tax for a citizen.

In any case, we would choose to limit our discussion to the economic analysis. So which is the better of the two? A brilliant paper by Haoyi Wang (2020) took a shot at this question to analyse the best way forward for China.

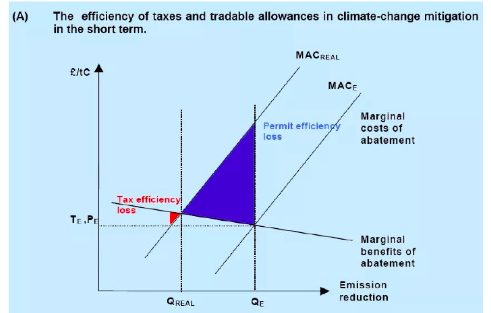

Wang analyses the two instruments in the short and long terms, in terms of what he refers to as :

1. Marginal cost of abatement (emission reduction):

Wang argues that in the short term for a corporate, the marginal cost of emission reduction is quite high. This is because of the higher costs of the removal or avoidance technologies which a corporate needs to invest in today, to reduce one unit of its emissions. However as time passes, the cost of these would drastically reduce due to technological advances and increased adoption. As a result the marginal cost of abatement is high in the short term, represented by a steep sloper and the slope becomes flatter in the long term.

2. Marginal benefit of emission reduction:

On the other hand, the marginal benefit is lower in the short term due to emission reductions creating little value for corporates due to relatively lower prices of these allowances. However, with time as the cap becomes lower the allowance prices would soar higher, thereby increasing the marginal benefit from each unit of emission reduction for negative emitters. Consequently, the marginal revenue curve is flatter in the short term, but becomes steeper with time.

The resulting dynamic for the short and the long term is depicted as below:

Short-term:

(Steeper marginal cost of abatement + Flatter marginal benefit of reduction)

The red area depicts the efficiency change in case of carbon tax regime, which is much smaller in area than the blue area depicting change in efficiency in case of permits (or ETS). This reflects that in the short term, ETS is more efficient in the short term than carbon tax.

Note: Loss here is to signify the change in efficiency going from expected to real-life scenario. We are concerned about the absolute value of that change, hence the larger area represents a higher change (increase in efficiency). For further nuances, check the paper here.

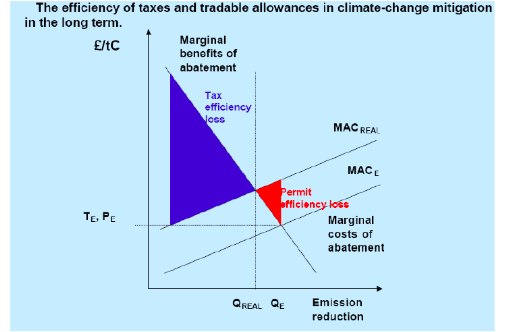

Long-term:

(Flatter marginal cost of abatement + Steeper marginal benefit of reduction)

This time, we see a higher area of the curve or efficiency change in case of a carbon tax regime w.r.t. a lower area or efficiency change in case of an ETS. This establishes that in the long term, carbon tax is more efficient than an ETS regime.

Conclusion

From an economic perspective, we do find an argument for a ETS regime in the short term that gradually shifts to a carbon tax regime as the most efficient carbon pricing mechanism. The author's suggestion is actually being implemented in China, with China ETS flourishing as we speak soon to become the largest ETS market in the world overtaking the oldest and largest EU ETS.

However, the fact that countries have resorted to varying combinations of the two (refer to the map at the start), tells us that economics is just one of the many lenses (though the most crucial one) in the complex geo-political landscape of a nation which may impact their ultimate choice.

![[object Object]](/lib_ubcXiSgTRmkLVyyT/k8w528b9mk1p20to.png?w=400)